Not long ago I was listening to a lecture devoted to Tolkien’s artistic languages such as Quenya or Sindarin that he created for his Legendarium of the Middle Earth. I have long been an avid reader of everything that came from Tolkien’s imagination and it has formed to a significant degree my own thinking and deepest intuitions. So as I was listening to this lecture it suddenly dawned on me that there is a very firm philosophical foundation underlying Tolkien’s philological creativity and as you dive deeper into Tolkien’s understanding of language, this philosophy takes over your own sensibilities. But first a bit of philosophical introduction.

Since the late Middle Ages we inhabit an increasingly nominalist worldview, i.e. we very often think that the names we attach to things are a consequence of arbitrary categorization by our minds and therefore this categorization is not inherent to the things themselves. E.g. we call things green not because the things we consider green have an inherent “greenness” that can be discerned within them, but because we arbitrarily lump together things that could be categorized differently and equally legitimately. Long story short, the resulting worldview is strongly subjective and relativistic. The “name” of a thing is a question of convention.

What is striking in Tolkien’s approach to language creation is that he insists that there is a certain fittingness of the sounds he settles for to name a thing. In the course of his designing of Quenya and Sindarin he repeatedly changed and adjusted forms of the words he had come up with so that they expressed better the meanings they were supposed to convey. The idea was that e.g. the Quenya word alda expresses in the most beautiful manner the “treeness” of the thing it designates, i.e. a tree. Tolkien constantly looked for sounds that would serve the meaning best and this quest of his was grounded in what he termed as “euphony” or “phonoaesthetics”. According to this idea the sounds of human language have a potential for beauty and for an appropriate expression of meanings.

In other words in Tolkien’s language creation we encounter a different worldview in which rational creatures are capable of naming things in accordance with their nature. The world is filled not with disparate entities, but by beings that have something real in common – certain natures – and language really attempts at reflecting these natures in a fitting way. This vision gains an especially attractive embodiment in Tolkien’s description of the elves, for the elves excel at naming things euphonically, that is with a beautiful and appropriate sounds. A language, however, is not a private enterprise but a common good, shared and used by all. Here emerges the idea of intersubjective realism. It’s true that an elf can consider a certain string of sounds as appropriate for a thing, but for a word to enter the common vocabulary it has to be approved by the community. So the sense of the beauty of particular sounds experienced by one rational creature is confronted by the sense of beauty of other creatures. This way the whole community discerns the proper names for things and comes at a phnoaesthetic consensus (usually by acclamation, in Tolkien’s world).

The things therefore have natures, these natures are accessible by reason and especially by an aesthetic “taste” of a person, and they can be expressed in a concerted intersubjective effort of rational creatures to name them. This is a beautiful literary embodiment of philosophical realism. When I first stumbled upon Tolkien’s works in my early teenage years I didn’t know a thing about realisms and nominalisms, but this Tolkienian vision of reality and its relationship to rational creatures so artfully turned into a narrative in his Legendarium made great impression on me back then. Only today I am able to recognize its influence on my thinking and reasoning, and especially on the first principles of my thinking as well, as on my philosophical “taste”. This proves how truly great literature is essential to laying down unconscious foundations of personality that will sustain it through the course of a person’s life. Many a time these unconscious foundations saved me from an existential crisis and I don’t doubt they will do this again in the future.

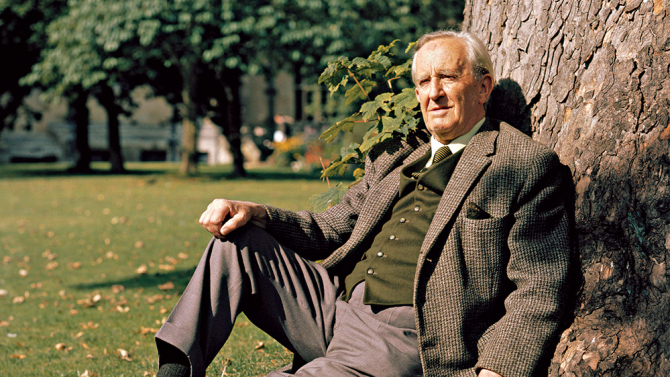

As we commemorated Tolkien’s death almost a week ago (2nd of September), it is appropriate at this point to say with thanksgiving this short prayer for him:

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. Requiescat in pace. Amen.

Or perhaps in Quenya:

Oia sérë á anta sen, Héru, ar oia cala nai sen caluva tennoio. Nai seruva sívessë. Násië.